- Home

- Hidden Details

- Nicholas Winton

Nicholas Winton in Prague: A Quiet Hero and the Children He Saved

Have you ever heard of the story of Nicholas Winton in Prague? The unknown humanitarian? If not, that's understandable. His story was kept a secret for about 50 years.

Maybe this sounds like an exaggeration, but I like to think that Winton, an Englishman, performed one of the greatest humanitarian acts of the 20th century.

He helped transport and save 669 children, most of them Jewish, from almost certain death during the Holocaust - from Czechoslovakia to Britain.

Today, you can find this bronze sculpture depicting Winton standing with two children on platform 1A in Prague's main station (Hlavní nádraží).

A Humble Beginning to a Heroic Tale

Sometimes I get caught up in the highlights of a story. Like a film, my thoughts compress time and it's easy to ignore the mundane details of its back story.

But it took enormous amounts of effort, and paperwork, and will power to get the children out of the country.

And Nicholas Winton didn't have any bureaucratic experience. In 1938, he was a stockbroker living a good life in London.

As he prepared for a ski holiday in Switzerland in December 1938, a friend working in Czechoslovakia urged him to come to Prague instead. Winton had already been following the news of refugees, but instead of heading to the Alps he went to Prague. And, what Winton saw there would change his life forever.

Czechoslovakia had recently been occupied by Nazi Germany following the Munich Agreement and thousands of Jewish refugees were pouring into Prague. Unfortunately there were no formal evacuation programs in place for children like the Kindertransport from Germany and Austria to Britain.

Recent Articles

-

Prague Hotels Near Charles Bridge – My Top Picks in the City Center

Feb 15, 26 12:10 PM

Prague hotels near Charles Bridge offer charm and unbeatable access to the city’s top sights. Enjoy a short walk of this iconic landmark and Old Town. -

Best Prague Hotels With Spa: Practical Options for a Relaxing Stay

Feb 03, 26 03:06 AM

Looking for a Prague hotel with a spa? This guide explains what to expect and highlights hotels where the wellness facilities are genuinely worth booking. -

Best Prague Hotels With Balcony: Honest Picks and What to Expect

Feb 01, 26 04:12 AM

Prague hotels with balcony options are rare. See which hotels offer balconies people love, what views to expect, and how to book the best room for you.

Nicholas Winton in Prague: The Rescue Effort Begins

In Prague, Winton quickly set up an office in a hotel in Old Town. And within days, anxious parents were lining the hallways, desperate to get their children to safety.

To help make their case, Winton photographed each child and assembled detailed profiles. These would be sent to England, in hopes of finding foster families willing to open their homes.

Returning to London, Winton launched a relentless campaign with a small group of people to assist him. They made phone calls and knocked on doors to meet the requirements set by the British government. Each child needed a host family and a £50 guarantee to cover any potential public costs.

It was a mountain of logistics. But Winton personally matched children with foster homes, secured travel documents, and worked through red tape to obtain exit visas, all as Europe edged closer to war.

As Winton admits in this 60 Minutes interview, he even forged documents and used a bit of deceptive ingenuity to push the process forward.

I love his matter-of-fact statement in that interview:

If something's not impossible, there must be a way of doing it.

In total, Winton organized eight trains that left Prague’s Wilson Railway Station between March and August 1939.

A ninth train, scheduled to leave on September 1, the day Germany invaded Poland and World War II officially began, was stopped. Most of the 250 children on that train were never seen again.

A Life of Silence and a Rediscovered Legacy

You could describe Nicholas Winton's actions as heroic.

But, how do we describe this part of the story...?

For decades, Nicholas Winton told no one, not even his wife, about what he had done.

It wasn’t until 1988, nearly 50 years later, that his story came to light when his wife, Grete, discovered a scrapbook in their attic. The book was filled with lists of children, photographs, and letters from parents.

She then passed the materials on to a Holocaust historian, and soon after, Winton was invited to appear on the BBC television program That’s Life!.

Check out this clip as the host surprises Winton with a powerful moment.

The Prague Connection

Praha hlavní nádraží (Prague Main Station), formerly Wilson Station served not only as a physical point of departure but also as a gateway between life and death. For those who managed to board the trains, it marked a narrow escape from the horror of the Holocaust.

Today, the station's tracks haven't been changed much. The train shed high above my head is the same. I can't visit without thinking about carriages of children being sent out of the country. They didn't know where they were going or for how long.

Those same children came from nearby neighborhoods - the same that I wander and explore without fear or thought of occupation, work camps, or daily brutality that citizens witnessed in 1939.

Thankfully Nicholas Winton, in Prague, had the courage to do something about what he saw.

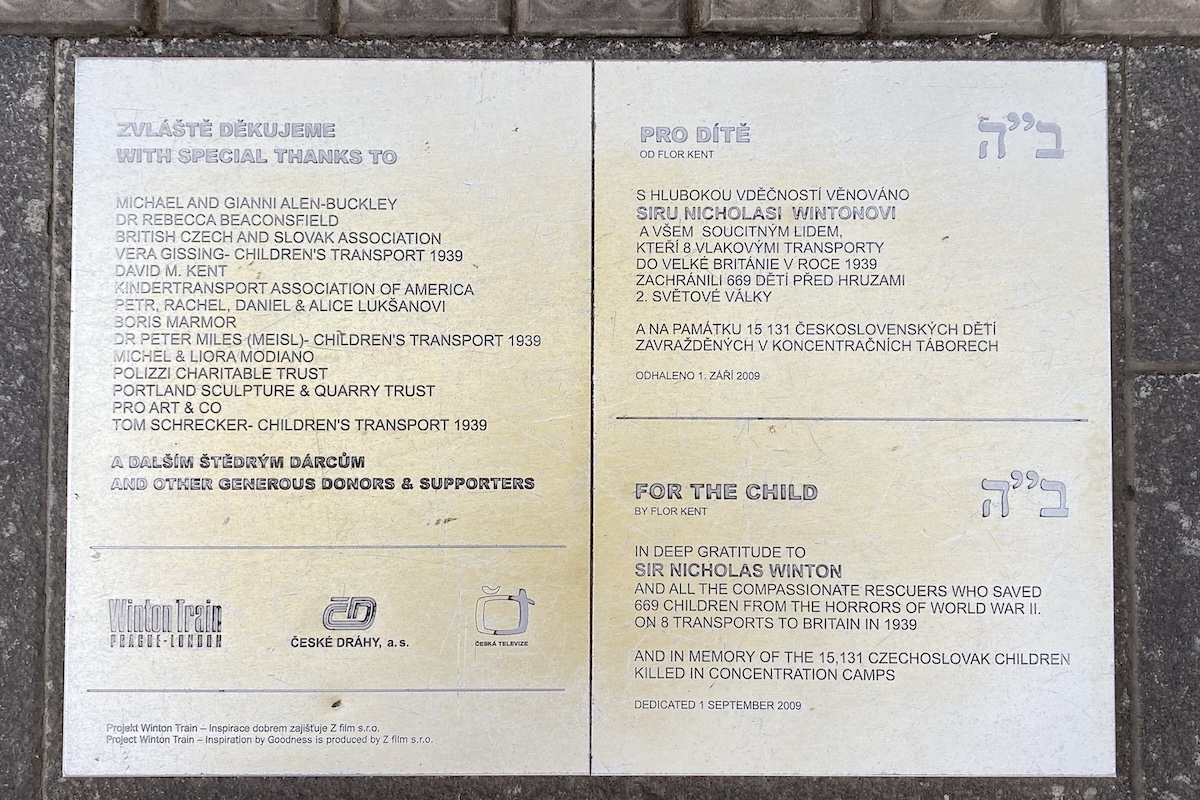

The statue of Nicholas Winton in Prague was unveiled at the station in 2009. Created by sculptor Flor Kent, it shows a young boy and girl standing beside Winton, who gazes quietly into the distance, suitcase at his side.

It's not just a tribute to Winton, but to the 669 children whose lives he changed, and the thousands more he wished he could have saved.

If you've been to the station, it's easy to miss. It stands off to the side in a quieter area next to the commuter rail line.

Find it by taking the first underground exit, pointing to '1A.' Once you're on the platform, walk to the far right side, with the station behind you. The sculpture stands near the first track, a few steps from the station's wall.

Plaque below the Nicholas Winton statue in Prague's station

Plaque below the Nicholas Winton statue in Prague's stationLegacy & Honors

In the years that followed, Winton received numerous honors, including an Order of the White Lion in Prague to a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II. He was also nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

In 2009, a ‘Winton Train’ retraced the original route, carrying survivors and their descendants through Europe.

Despite the accolades, Winton remained characteristically modest. Saying, “Why are you making such a big deal out of it? I just saw what was going on and did what I could to help.”

In 2015 at the age of 106, Winton passed away - on the 76th anniversary of the departure of one of the Kindertransport trains he organized.